A Quantitative Model of Human Jejunal Smooth Muscle Cell Electrophysiology

Abstract¶

The Poh et al. (2012) paper describes the first biophysically based computational model of human jejunal smooth muscle cell (hJSMC) electrophysiology. The ionic currents are described by either a traditional Hodgkin-Huxley (HH) formalism or a deterministic multi-state Markov (MM) formalism. We create a modularized CellML implementation of the model, which is able to reproduce clamping behaviours of individual currents and whole cell action potential traces. In addition, some inconsistencies have been uncovered and discussed in this paper.

1Introduction¶

In the primary paper Poh et al., 2012, the first biophysically based model of human jejunal smooth muscle cell (hJSMC) electrophysiology was presented. Here, we divide the mathematical model into distinct sub-modules encoded in CellML enabling reuse of the various sub-modules in future studies and models. We attempt to reproduce individual ionic currents, cellular voltage behaviour and sensitive analysis corresponding to changes of channel conductance. From the primary paper we extracted data using the Engauge digitizer software Mitchell et al., 2020 to compare the current simulation results against those in the primary publication. In doing so, we found inconsistencies in parameter values and mathematical equations presented in the primary paper, as well as the simulation experiment settings. These discrepancies are discussed in Section 4.

2Model description¶

2.1Primary Publication¶

In the hJSMC model Poh et al., 2012, L-type calcium channels, the large conductance calcium and voltage activated potassium channels (BK) channels, and sodium channels are formulated using a deterministic multi-state Markov (MM) model Sakmann & Neher, 1996, while the T-type calcium channels and voltage dependent potassium current employ a traditional Hodgkin-Huxley (HH) formalism Hodgkin & Huxley, 1952. The sodium calcium exchanger and sodium potassium pump formulation are based on the work proposed by Tusscher et al. (2004). The primary publication shows that the model has been validated against a wide range of experiments and data. The authors also provide CellML code https://

2.2Modularized CellML model¶

The modularized version of the CellML implementation is available on Physiome Model Repository (PMR) at https://

The membrane potential component defines the complete equations of the membrane potential and total ionic current. It combines the imported ionic current components and ionic concentrations components. The component can be stimulated by various periodic stimuli and generates a sequence of action potentials. The clamped current component defines the complete equations of the total and individual ionic currents, when performing voltage or concentration clamp simulation experiments.

The individual ionic current components share the same formulation , where is the membrane potential and is the reversal potential defined in the Nernst potential component. The open probability computation depends on the formalism. For L-type calcium channels, the large conductance calcium and voltage activated potassium channels (BK) channels, sodium channels, a deterministic multi-state Markov (MM) model Sakmann & Neher, 1996 is used to describe various channel states. Such currents incorporate the channel states components. The Hodgkin-Huxley (HH) formalism of the T-type calcium channels and voltage dependent potassium current includes the gating kinetics components along with steady state of gates and time constants components. The sodium calcium exchanger and sodium potassium pump formulation is different from the aforementioned currents, which is defined in its own component.

The ionic concentrations component defines the dependence of the intracellular concentrations on the membrane currents. The temperature factor component encodes the temperature coefficient , where is species specific parameter, is the reference temperature (i.e., the model construction temperature), and is the desired temperature for a given simulation experiment. This coefficient is included in the equations listed in Table 3.

Following best practices, our CellML implementation separates the mathematics from the parameterisation of the model. The mathematical model is imported into a specific parameterised instance in order to perform numerical simulations. The parameterisation would include defining the stimulus protocol to be applied. We have three sets of simulation experiments and corresponding simulation results to reproduce the corresponding figures in the primary publication:

- the patch clamp experiment is used to validate the individual ionic currents;

- the periodic stimulation experiment is used to generate a sequence of action potentials; and

- the sensitivity analysis experiment is used to evaluate the contributions of currents to the membrane voltage.

Simulation settings and detailed solver information are encoded in SED-ML documents for execution of the simulation experiments Waltemath et al., 2011. The Python scripts used with OpenCOR Garny & Hunter, 2015 to perform simulations and produce the figures in the primary paper are also included in the folder <Simulation>. The name of the simulation and plot scripts indicate the figure number in the primary paper. For example, Fig2_sim.py is used to generate the simulation data and Fig2_plot.py reproduces the graph shown in Figure 2 from Poh et al. (2012).

3Model results¶

3.1Response of individual ionic currents to clamped voltage¶

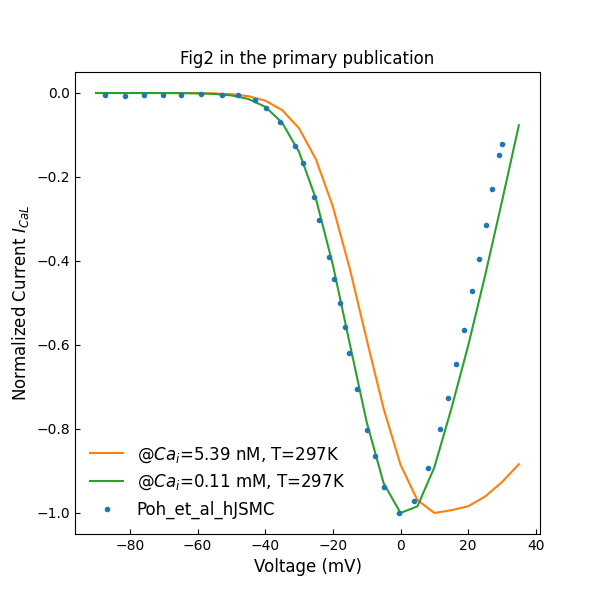

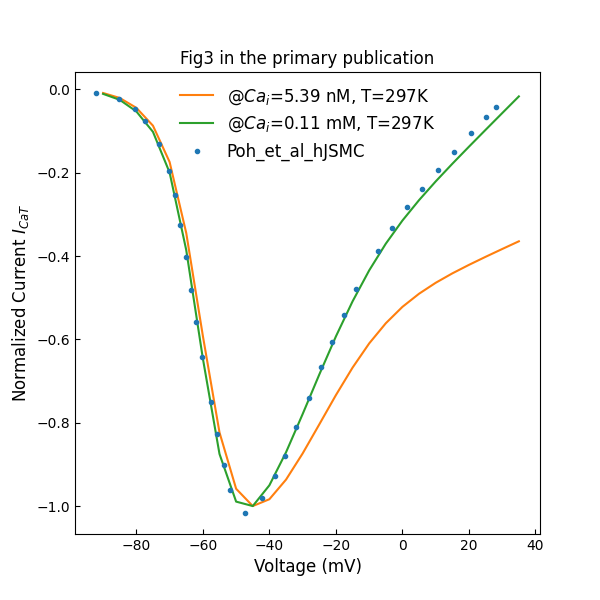

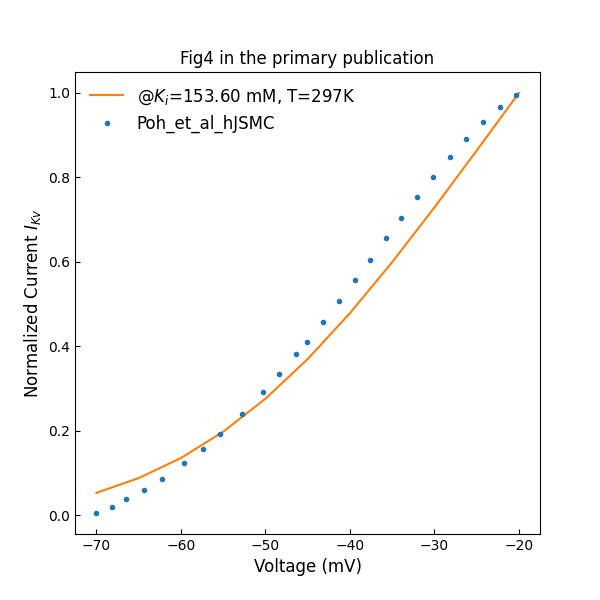

In the patch clamp experiment, the clamped current component is configured and parameterised with an applied patch clamp protocol. The clamping parameters can be changed by the user, while the values used in this article are listed in Table 1. The holding voltage duration is second and the temperature is Kelvin. The simulation experiment can be performed by loading the corresponding SED-ML document into OpenCOR and executing the simulation. By increasing the intracellular concentrations, we have reproduced the IV curves in Figures 1, 2 and 5, however, the specific experiment settings cannot be confirmed by the authors.

Table 1:Clamping parameters

| Fig | Holding voltage (mV) | Test voltages (mV) | Current | (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | -100 | -90:5:40 | , | |

| 3 | -100 | -90:5:40 | , | |

| 4 | -70 | -70:5:-15 | ||

| 5 | -70 | -70:10:70 | , , | |

| 6 | -100 | -90:5:30 | , |

In the presented figures, the dots denote the simulated data extracted from the primary publication, while the solid lines are the simulation results produced by the current CellML implementation.

Figure 1 shows the normalized L-type channels peak I–V plot with different intracelluar concentrations. During simulation, the and in Equations S-33 and S-34 are set to 0 to switch off the dependency. Figure 2 shows normalized T-type channels peak I–V plot.

Figure 1:Normalized L-type channels peak I–V plot (c.f., Fig. 2 in Poh et al. (2012)).

Figure 2:Normalized T-type channels peak I–V plot (c.f., Fig. 3 in Poh et al. (2012)).

Figure 3 shows normalized I–V plot of whole cell voltage-activated potassium currents. The holding voltage was not specified in the primary paper, and we assume here a value of mV.

Figure 3:Normalized I–V plot of whole cell voltage-activated potassium currents (c.f., Fig. 4 in Poh et al. (2012)).

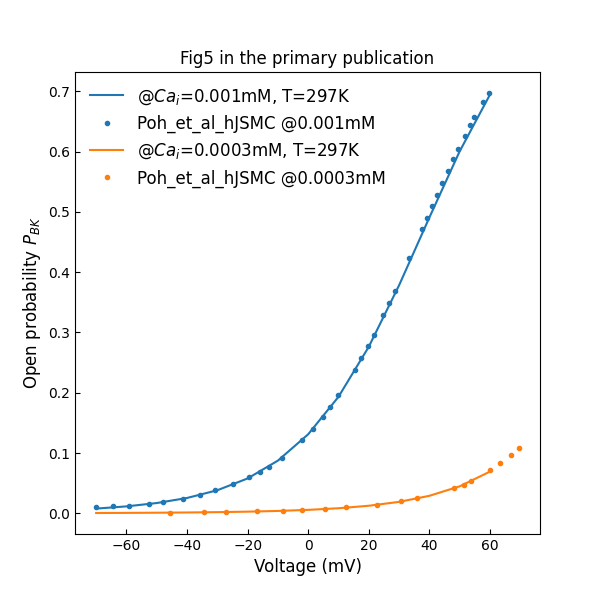

Figure 4:Open probability versus clamping voltage plots, across various free intracellular concentrations (c.f., Fig. 5 in Poh et al. (2012)).

Figure 4 shows open probability of BK channel versus clamping voltage at various intracellular calcium concentrations.

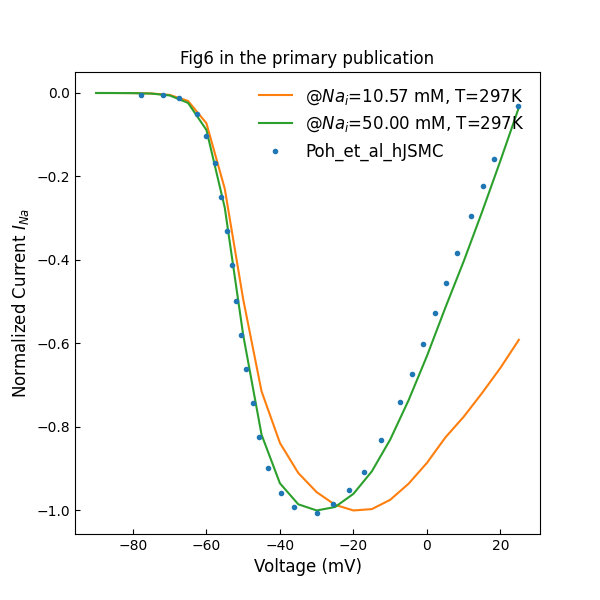

Figure 5 shows normalized sodium channel peak I–V plot various intracellular concentrations.

Figure 5:Normalized channel peak I–V plot (c.f., Fig. 6 in Poh et al. (2012)).

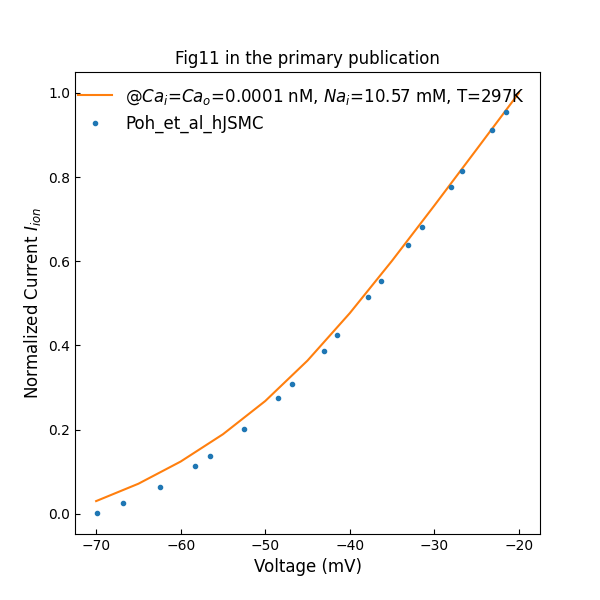

Figure 6:Simulated whole cell normalized I–V data under near calcium-free conditions (c.f., Fig. 11 in Poh et al. (2012)).

Figure 6 shows whole cell normalized I–V data from hJSMC model under near calcium-free conditions. The intracellular concentration is set to 10.57 mM, while the value is unknown in the primary publication.

3.2Simulated action potentials¶

In the periodic stimulation experiment, the membrane potential component is configured and parameterised with a periodic stimulus current. The parameters of stimulation can be changed and the following simulation uses 310 Kelvin for the temperature setting.

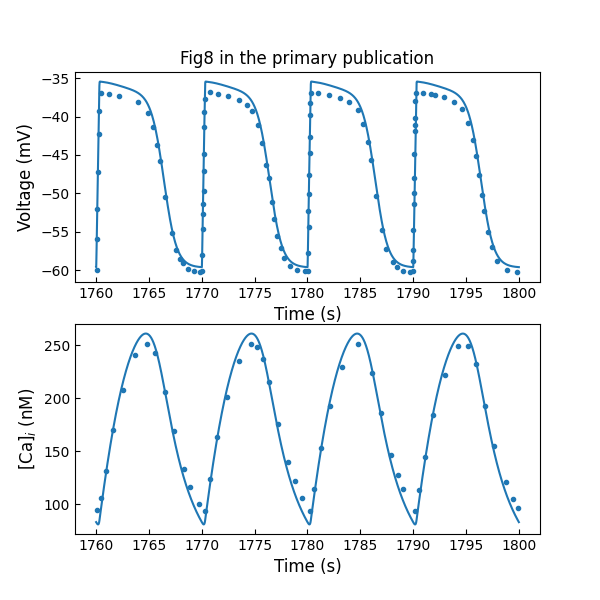

Figure 7 shows the simulated hJSMC action potential trace and free intracellular calcium concentration after a simulation of 30 minutes of electrical activity.

Figure 7:simulated hJSMC action potential trace and free intracellular calcium concentration after a simulation of 30 minutes of electrical activity (c.f., Fig. 8 in Poh et al. (2012)).

3.3Sensitivity Analysis¶

In the sensitivity analysis experiment, the membrane potential component is configured to accept the changes of maximum conductance of ionic channels in the component g_parameters.

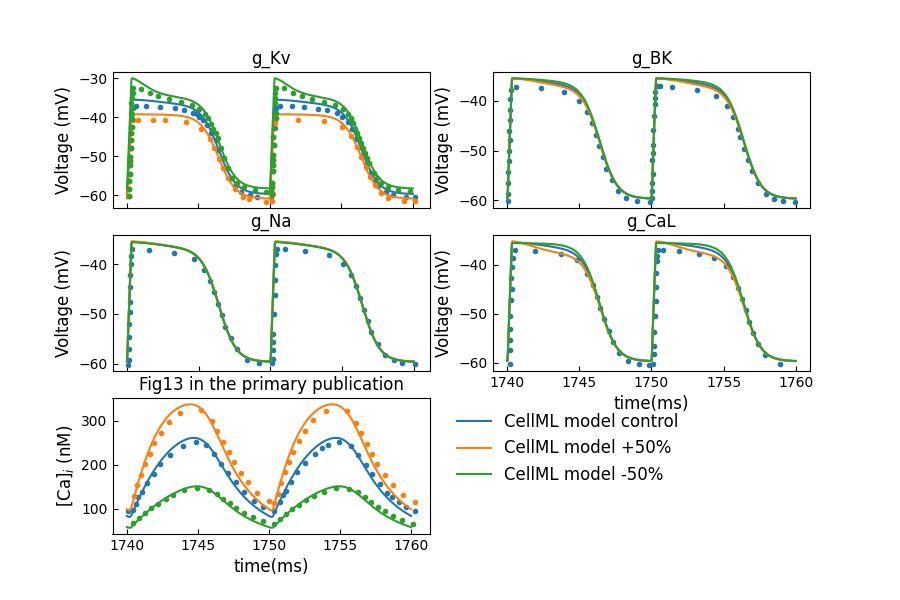

Figure 8 shows sensitivity analysis by 50% increase or decrease in maximum channel conductance. This evaluates the contributions of key ionic currents towards hJSMC membrane voltage. The last plot shows the free intracellular concentrations corresponding to changes in .

Figure 8:Sensitivity analysis by 50% increase or decrease in maximum channel conductance (c.f., Fig. 13 in Poh et al. (2012)).

4Discussion¶

Based on the author provided model implementation Poh et al., 2012, we modularized the CellML implementation for reusability. Additionally, we added clamped current component, patch clamp protocol and voltage clamp experiment to simulate ionic currents during a voltage clamp. We also modified the periodic current protocol and periodic stimulation experiment to enable the periodic stimulation for Figure 8.

During the curating process, we found some parameters (see Table 2) and equations (see Table 3) which are inconsistent from the ones presented in the primary publication.

Since the clamping values for intracellular concentrations of , and were not specified in the paper, we used the initial values presented in the original CellML model in the first attempt. However, the difference becomes significant at less negative clamping voltages when reproducing the original Figures 2, 3, and 6. We then increased the intracellular concentrations for a better fit. However, the values of intracellular concentrations in particular are quite larger than physiological value, which should be aware of in future usage of this model.

Table 2:Inconsistency of parameters

| Parameters | primary paper | Original CellML | C code | current CellML |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1852 | 9.26 | 16.197 | 16.197 | |

| 1.9058 | 1.9058 | 1.9508 | 1.9508 | |

| 1st factor in Eq(S-24) | 0.05956 | 0.05956 | 0.005956 | 0.005956 |

Table 3:Inconsistency of equations

Equations | primary paper | Original CellML | C code | current CellML |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-5, S-6, S-7 | without unit conversion | in and | ||

| S-13, S-14 | No T[1] | with T[2] | with T[3] | with T[4] and |

| S-23,..., S-28 | No T[5] | with T[6] | with T[7] | with T[8] and |

| S-33, S-34 | No T[9] | with T[10] | with T[11] | with T[12] and |

| S-36, S-37, | No T[13] | with T[14] | with T[15] | with T[16] and |

| S-43, S-44 | No T[17] | with T[18] | with T[19] | with T[20] and |

| S-80,..., S-91 | No T[21] | with T[22] | with T[23] | with T[24] and |

| S-67,..., S-70 | with | without | without | without |

| S-75,..., S-78 | with | without | without | without |

Acknowledgments¶

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Alberto Corrias and Martin Buist in the validation of the model implementation presented here.

- Poh, Y. C., Corrias, A., Cheng, N., & Buist, M. L. (2012). A quantitative model of human jejunal smooth muscle cell electrophysiology.

- Mitchell, M., Muftakhidinov, B., Winchen, T., Wilms, A., Schaik, B. van, badshah400, Mo-Gul, Badger, T. G., Jędrzejewski-Szmek, Z., kensington, & kylesower. (2020). markummitchell/engauge-digitizer: Nonrelease. Zenodo. 10.5281/zenodo.3941227

- Sakmann, B., & Neher, E. (1996). Single-channel recording. General Pharmacology: The Vascular System, 27(6), 1078. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-3623(96)90073-7

- Hodgkin, A. L., & Huxley, A. F. (1952). A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. The Journal of Physiology, 117(4), 500–544.

- ten Tusscher, K. H., Noble, D., Noble, P.-J., & Panfilov, A. V. (2004). A model for human ventricular tissue. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 286(4), H1573–H1589.

- Waltemath, D., Adams, R., Bergmann, F. T., Hucka, M., Kolpakov, F., Miller, A. K., Moraru, I. I., Nickerson, D., Sahle, S., Snoep, J. L., & Novère, N. L. (2011). Reproducible computational biology experiments with SED-ML - The Simulation Experiment Description Markup Language. BMC Systems Biology, 5(1), 198. 10.1186/1752-0509-5-198

- Garny, A., & Hunter, P. J. (2015). OpenCOR: a modular and interoperable approach to computational biology. Front Physiol, 6. 10.3389/fphys.2015.00026